When Charlotte Braithwait, a 38-year-old bookkeeper from Owasso, Oklahoma, began feeling her heart beat erratically in the fall of 2023, she knew something wasn’t right.

Unlike many people with atrial fibrillation (AFib), Braithwait could feel her heart fluttering—like it was bouncing around inside her chest. “It wasn’t just once or twice,” she said. “It kept happening.”

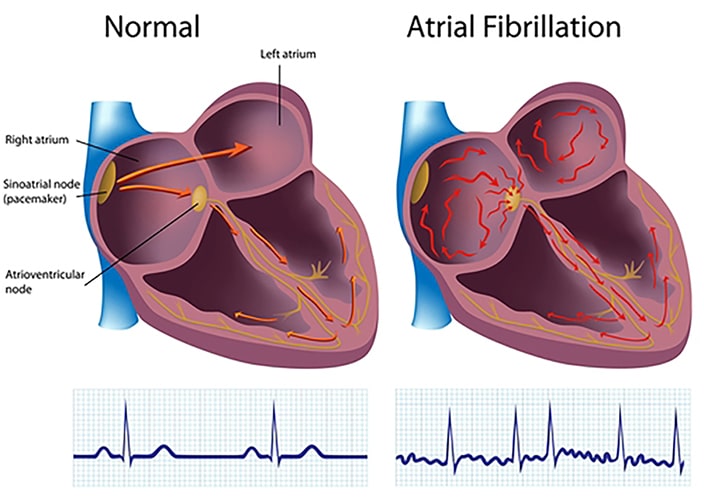

AFib is a common heart rhythm disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. It causes the heart to beat irregularly, which can lead to blood clots, stroke, heart failure and other complications.

Symptoms may vary, but often include fatigue, dizziness, shortness of breath, and a fluttering sensation in the chest.

Heart monitoring

Braithwait’s journey began with a visit to her doctor in December 2023. She was fitted with a heart monitor that she wore continuously at home for several weeks. The results confirmed what she suspected: she had AFib.

What made Braithwait’s case unique was her lack of traditional risk factors. She had no history of high blood pressure, sleep apnea or coronary artery disease. Instead, she believes her AFib is hereditary. “My grandma had it. My dad has it. My uncle has it,” she said. “It must be in my genes.”

After her diagnosis, Braithwait met with Megan Renz, APRN-CNS, who discussed treatment options. While medications are often the first line of defense, they come with risks. One drug, for example, could dangerously lower her heart rate — a concern given Braithwait’s active lifestyle. “I jog and exercise almost every day,” she said. “That medicine wasn’t a good option for me.”

Braithwait tried a low-dose medication, but it didn’t help. That’s when Renz suggested an ablation—a procedure that targets the heart tissue causing the irregular rhythm. Initially hesitant, Braithwait canceled her first scheduled ablation, hoping to find a fix through blood tests or lifestyle changes. But she soon learned that AFib is more about the heart’s electrical system than blood chemistry.

Cardiac ablation

In January 2025, Braithwaite underwent a newer type of ablation called Pulsed Field Ablation (PFA). Unlike traditional methods that use heat (radiofrequency) or cold (cryoablation), PFA uses electrical pulses to target heart tissue with fewer risks.

Braithwait’s cardiologist, David A. Sandler, MD, explained the differences between the procedures and recommended PFA for its safety profile. “He was super personable and knowledgeable,” she said. “I researched it, prayed about it, and decided it was the right choice.”

Since then, Braithwait reports feeling much better. While she occasionally notices minor fluttering, her heart no longer slips into AFib. “It’s not consistent, and it’s not a huge issue anymore,” she said. “After the ablation, I don’t have that problem, which is a blessing.”

Her active lifestyle hasn’t changed. She still runs three times a week—up to five miles outdoors—and does strength training on other days. She and her husband, married for 18 years with four children, are even planning a cruise this fall.

Reflecting on her experience, Braithwait expressed deep gratitude. “I realized after my appointment that I didn’t even say thank you,” she said. “So, thank you, Dr. Sandler and the whole team. I’m so grateful I don’t have to deal with AFib for (hopefully) the foreseeable future.”

Braithwait’s story is a reminder that AFib doesn’t always follow the rules. It can affect healthy, active people and may run in families. But with the right care, information and support, it’s possible to manage—and even overcome—this condition.

For more information about Oklahoma Heart Institute’s services or to find a physician, visit our website.